Notes from southern Argentina where BP controls the main oil company

by Hernán Scandizzo / OPSur

Access to drinking water is not a new problem in the city of Comodoro Rivadavia or in the San Jorge Gulf. Some in the Argentine Patagonia, in the province of Chubut and northeast of Santa Cruz, experience it from birth. A widely circulated -and equally challenged- version of the discovery of oil in Comodoro Rivadavia in December 1907 attributes it to random fact: the hydrocarbons sprouted when a well was drilled, more than 500 meters deep, in search of water. Fable or not, from that moment the incipient port town became the cradle of the Argentine petroleum industry and, over the years, became the national capital of petroleum.

A century later, in places like Comodoro Rivadavia, Rada Tilly, and Caleta Olivia, conflicts over water are constantly on the rise. It is no longer just a question of access to water in quantity, but also in quality, since there are suspicions about the salubrity of underground aquifers, drilled for 110 years of extraction of hydrocarbons. To add to this, the river Senguer has been losing flow, which was manifested in a clear way with the disappearance of Lake Colhue Huapi in 2016, affecting Lake Musters, which supplies about 500 thousand people through aqueducts.

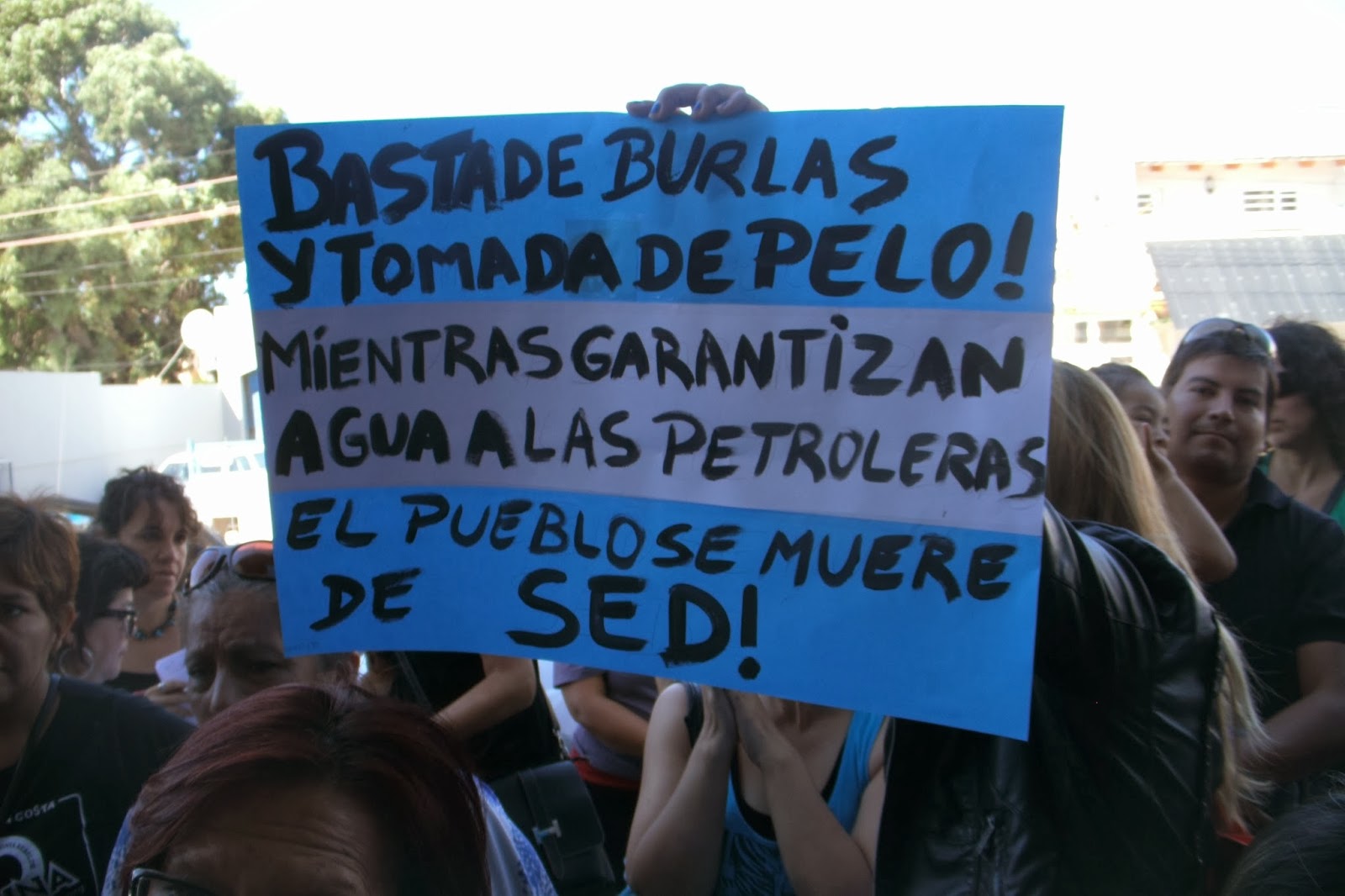

Public authorities in Chubut have tried to explain the situation as a consequence of the sharp decline of rains and snowfall, and mention natural “cycles” of the basin. In summary, for the authorities, “Nature” is the problem. Meanwhile, neighborhood assemblies and socio-environmental organizations in the region point the blame at the economic model: the mismanagement of water upstream of Lake Musters by the large agricultural establishments – which divert part of the flow to their fields – and oil companies, that require huge volumes to keep the mature fields in production through enhanced oil recovery.1

Turning to oil

After the drilling of that disputed well in Comodoro Rivadavia at the beginning of the 20th century, the extractive activity gradually relegated the agricultural sector to a marginal place, which was initially presented as a productive alternative in those lands. The same happened in the north of Santa Cruz, where the exploitation of the fields near Cañadón Seco first, and Las Heras later, determined the destiny of sheep farming alongside the ups and downs of the international price of the wool. Territory turned to the oil, wells multiplied by thousands. For national and provincial authorities, rent-seeking became a way of life, orientating public policies to this day to consolidate a monoproductory matrix centered on the extraction of hydrocarbons and energy generation.

“Three companies – Pan American Energy (PAE), YPF2 and Sinopec3 – account for 90% of the extraction in the San Jorge Gulf basin. YPF, with greater weight in Santa Cruz Norte, and PAE, with greater weight in Chubut, extract 38% and 39% of the oil; Sinopec contributes a bit over 10%, and the rest are fourteen companies that contribute the other 10%, “says Cesar Vicente Herrara, professor of Macroeconomic Policy and head of the Observatory of Natural Resource Economy of Southern Patagonia, Faculty of Economics, National University of Patagonia. The other companies operating in the basin are Enap Sipetrol Argentina, a subsidiary of Chile’s state-owned company; Tecpetrol, belonging to the Argentinean-Italian firm Techint; subsidiaries of US companies CRI Holding Inc and Apco Oil and Gas International Inc, and those of Argentine capital companies, Compañías Asociadas Petroleras SA, Unitec Energy, Petrolera Cerro Negro, Colhue Huapi SA, Petroquímica Comodoro Rivadavia, Alianza Petrolera Argentina, Roch SA, COPESA Cía Constructora Petrolera SA, Dapetrol y Petrominera Chubut, the last, is the state-owned company of Chubut.

The Dragon´s footprint

Towards the end of 1950, state oil compant YPF began drilling the oilfield Cerro Dragón, and immediately it was concessioned to the American Amoco. In September 1997, this company and Bridas, controlled by the Argentine family Bulgheroni, formed Pan American Energy LLC. The company was headquartered in Delaware, USA, and the shares were split 60-40, respectively. The following year Amoco merged with British Petroleum; later reduced its name to BP. Meanwhile, Bridas and CNOOC International – a subsidiary of China’s state oil company – formed the joint venture Bridas Corp. in 2010, in which both have equal shareholding and share in strategic decision-making.

Pan American Energy is the main operator with majority non-Argentine capital of the San Jorge Gulf. In 2014 Cerro Dragón, which is accessed mainly from the province of Chubut, accounted for 91% of the crude oil and 54% of the gas extracted by PAE. The field is clearly the backbone of the company in the country: 87% of its total proved reserves, according to the prospectus presented to the National Securities Commission of Argentina in 2015 by the British-Chinese-Argentine company. In 2016, 19% of the crude produced at the national level was extracted from Cerro Dragon. A third of the income of Chubut province comes from oil royalties, so that public coffers are heavily dependent on the sector and particularly on PAE.

Out of the more than 3700 wells used by the company, 70% are subject to secondary recovery processes; a percentage that extends to the whole basin, according to the Undersecretary of Hydrocarbons of Chubut province, Daniel Molina. In response to the widespread accusation that the water lacking in the homes is in the oil wells, PAE claims that its operations do not use fresh water, but reuses production waters.

More than a century passed since the drilling of the well that changed the history of the San Jorge gulf. Millions of barrels of crude and cubic meters of gas have been and are being taken from Earth’s entrails . Thousands built their lives around this activity; some became rich; the hydrocarbons and their derivatives got consumed in different parts of Argentina and beyond. A century has passed and problems with access to water is only worsen.

*Revised version of the article that began the series of articles On water and oil, questions about the present of San Jorge Gulf basin.

1Enhanced oil recovery basically consists of injecting water and chemicals, or gases, which contribute to ‘drag’ / ‘sweep’ the oil into the well and thus increase extraction.

2Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF) was founded in 1922 by the national government. During the neoliberal reform of the state of the 1990s it was privatized and in 1999 the Spanish oil company Repsol took full control of the company. In 2012, a 51% shareholding in YPF was nationalised, as a mixed capital company.

3In April 2017 the Chinese company Sinopec announced its withdrawal from Chubut, after the storm that generated heavy damages in Comodoro Rivadavia, shutting down operations in the area Bella Vista. Aside from the aftermath of the climate phenomenon, since the second half of 2016 the company decided not to renew its licence on the block. That same year it announced a project of exploration of shales in the area Piedra Clavada Sur, in the province of Santa Cruz.